- 28 Березня, 2019

- Posted by: East office

- Categories: Публікації, Російська криза, Тематика

Idel-Ural is a historical region in the East of the European part of the Russian Federation. Even now, being under the total control and pressure from Moscow, the peoples of Idel-Ural continue their struggle for national identity and sovereignty. The region remains a hidden geopolitical hotspot that can manifest itself in conditions of the current political turbulence.

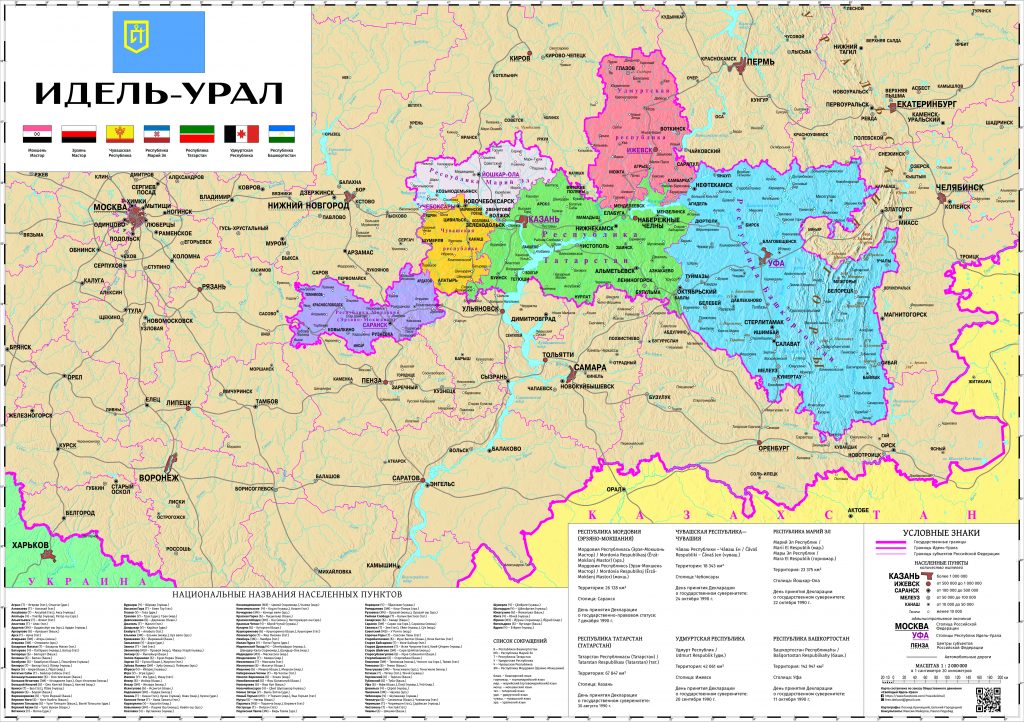

In the east of the European part of Russia there is a historical region which is called Povolzhye (region along the Volga River) by the Russians and Idel-Ural by the indigenous population. The region consists of six states: Erzia-Mokshania (Mordovia), Chuvashia, Mari El, Tatarstan, Udmurtia and Bashkortostan which have their own unique cultures created by seven indigenous peoples.

Finno-Ugrian peoples of Erzia, Moksha, Mari and the Udmurts live near their Turkic neighbours: Chuvashes, Tatars and Bashkirs. Idel-Ural states are so much different from the neighboring Russian regions that Moscow had to give each of them the status of an independent republic with its own constitution, state language and organs of governance. Today these republican attributes are rather a theatrical decoration which conceals harsh centralism and submission to Moscow.

It was not always like that. In the early 1990s, when the federal center was weak and irresolute, each of the republics obtained numerous sovereign rights. During that time national parties, civic and political organizations mushroomed, and there was hope that the republics can be let “float freely”.

Territory and demography of Idel-Ural

Idel-Ural is the territory where two worlds – the Turkic and the Finno-Ugrian cultures – meet and actively interact. Notwithstanding the differences in religion and cultural traditions, interaction of Turkic and Finno-Ugrian peoples did not give rise to bitter feud or isolationism. Quite the contrary, Idel-Ural can be called an integral space that preserves identity of the title nations for many centuries by presenting opposition to russification and blurring of ethnic, linguistic and religious lines.

All Idel-Ural republics are located in the eastern part of Europe. As of the beginning of 2019, they are parts of the Russian Federation. Erzia-Mokshania (Republic of Mordovia) is the westernmost

state of the region. The distance from the western border of Mordovia to the eastern border of Ukraine is around 500 km. In the east of Idel-Ural there is Bashkortostan – Europe’s easternmost

country. Total area of Idel-Ural is 320 708 km². Population of Idel-Ural is 12 189 127 people [1]. That goes to say that Idel-Ural’s territory is comparable to the territory of Poland (312 685 km²),

and its population is comparable to population of Greece (10 741 165 people) [2].

In 1919-1925 Bashkortostan, and thus Idel-Ural, had common border with Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (that was the name of Kazakhstan at the time). However, in 1925 Bolsheviks excluded Province of Orenburg from the Soviet Kazakhstan and gave it to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). Capital of Kazakhstan was transferred from Orenburg to Kzyl-Orda. Thus, the so-called Orenburg corridor which divided the two Turk republics was formed. At first the corridor that separated Kazakhstan from Baskortostan was only 30 km wide. The fear that friendship between Bashkirian and Kazakh peoples would become “too close” made Moscow “revise the borders” several times. As a result, the corridor increased nearly twofold. Today Idel-Ural republics have no exits to external borders, and the distance between the southern border of Bashkortostan and the northern border of Kazakhstan is approximately 50 km.

Tatarstan – leading political player in the region

Tatarstan is located in the geographical center of Idel-Ural. Being rich in natural resources, it has always aspired to both economic and political self-sufficiency. Although the Tatarian nation

was digested by Muscovy and now by the Russian Federation for half a millennium, the Volga Tatars managed to keep their identity, and now they serve as an example for their neighbours. The Tatars achieved great successes in development of culture – the first Tatarian book saw the light of day in 1612 (it was a Tatarian grammar book). Kazan has become an important book-publishing center of the Russian Empire. The books were published not only in Tatarian language, but also in the languages of almost all Idel-Ural peoples. One of the first measures of the sovereign Tatarstan in the early 1990s was foundation of the Tatarian Magarif Publishing House which has published one and a half thousand books with total circulation of 18. 5 mln copies in less than thirty years [3, 2].

Today, in addition to the republican authorities, a lot of volunteers work to further develop Tatarian science and culture. Not only classical works of the world literature (including the works of ancient philosophers), but also modern-day scientific studies in the fields of physics, mathematics, medicine, astronomy, etc., are translated to Tatarian language. The Tatarian translators work more with English and Turkish languages than with Russian language. In the last few years there appeared dozens of TED video lectures translated into Tatarian. There are even programming textbooks in Tatarian – it is something unimaginable for a majority of the indigenous peoples of the Russian Federation [4].

Such great achievements in development and preservation of the Tatarian culture would have been impossible without significant intellectual and financial resources. Resistivity of the Tatarian nation to assimilation processes is due to a number of the national features: determination, persistency, entrepreneurial skills, and belief in Islam in combination with maintenance of national traditions. The Tatarian infrastructure, education and science projects, together with meagre autonomy for implementation of its own humanitarian policy which Moscow begrudgingly granted to the republic, show that Tatarstan is very important for the Russian economy. Every year the republic appears in the TOP-10 of the most economically developed constituent entities of the Russian Federation. Tatarstan is a region where important industries are concentrated: oil production and oil processing, aircraft engineering, communication, production of explosives, machine-building, car production. Important Russian infrastructure facilities are located on the territory of the republic: oil and gas pipelines, two international airports, railway lines, bridges across Volga and Sviyaga. [5, 20–21].

For many centuries Moscow tried to neutralize the Tatarian drive for revival of sovereignty by involving the Tatarian people in the process of Russia’s expansion (Russian Empire, the USSR and later the RF). However, with the onset of Perestroika the desire to restore the Tatarian nation reappeared. In 1988-1990 Tatarstan saw appearance and development of political parties, civic organizations and movements which Moscow could not control: Tatarian Civic Center. Azatlyk Youth Alliance, the Party of Tatar National Independence Ittifak, Milli Mejlis (a self-proclaimed pan-Tatar parliament established to create opposition to the republican parliament which was controlled by the Communists), etc.

Founded in April 1990, the Ittifak Party (“ittifak” is “harmony” in Tatarian) openly declared that it had intentions to fight for the sovereignty of the republic. The party quickly gained popularity among Tatarian urban intellectual class and radical youth. Tatarstan was the first among the republics of IdelUral to declare independence (30. 08. 1990) and to proclaim its intention to be a self-sustained sovereign state. In 1991 in the RSFSR presidential elections were held; Tatarstan was also electing the President of the republic. Tatarian radical circles supported by the official Kazan authorities tried to boycott elections of the President of Russia on the territory of the republic. As a result, 36. 6% of Tatarian voters took part in the election of the President of Russia, and 65% – in the election of the President of Tatarstan. In Tatarstan Boris Yeltsin received 16. 5% of the votes, and Mintimer Shaimiev – 44. 8% [6, 4].

At first, in 1990 the party nomenclature of Tatarstan tried to ignore the new political players. Later, in the first half of 1991 the Communist-led officialdom of Tatarstan made an attempt to use national movement in its “game of counterweights” with Moscow spooking the Kremlin with the nationalists coming to power and claiming that dialog with the latter would be impossible. However, in December 1991 positions of the Tatarian national movement represented first of all by the Tatarian Civic Center and the Ittifak Party strengthened: individual organizational units were made larger, managerial personnel for local party cells were prepared, publication of their own periodicals got underway.

On October 24, 1991 Tatarstan has declared sovereignty. Independent status of the republic was confirmed by referendum in 1992. Soon after that Tatarstan refused to sign the Federal Agreement

and even approved its own constitution [7]. Up to the early 1994 Tatarstan tried to carry out its independent policy balancing between the ideas of complete independence and maintenance of

economic links with Russia. Finally, under pressure from Moscow Shaimiev caved in: on February 1994 the Agreement of mutual delegation of authority has been concluded between Tatarstan

and the Russian Federation. In accordance with this Agreement, Tatarstan became an associated country unified with Russia within a confederation. From that moment on Kazan tried to keep its

sovereignty which dwindled over the years, meanwhile Moscow overmastered Tatarstan with its resources still further.

Exceptional role of Bashkortostan

One of the reasons why Kazan has lost in its political confrontation with Moscow was the fact that Tatarstan had no common borders with independent states. In the early 1990s Idel-Ural was surrounded on all sides by “Russian sea”, and it could have exit to an external border only in the south.

Unlike Tatarstan, Bashkortostan entered Perestroika under quite different initial conditions. The Bashkirs inherited a whole lot of ethnic and territorial problems from Stalin’s national policy. The modern-day borders of the Republic of Bashkortostan differ greatly from Bash Kurdistan for which the Bashkirian national hero Ahmet Zakie Validi has been fighting in 1919. At that time, one hundred years ago the Bashkirian Republic (Bash Kurdistan is another official name) included the eastern part of today’s Bashkortostan and several enclaves in the south and in the east. Bash Kurdistan had no towns, its capital was in the village of Temyasovo. At the same time, the republic had an advantage – relatively high level of ethnic homogeneity – over 60% of population were Bashkirs [8].

However, in 1921, when Ahmet Zaki Validi has emigrated, the new head of the Bashkirian government Mulayan Khalikov asked Moscow to expand the Bashkirian borders. Eventually, Bashkortostan was given vast territories with towns, quarries, railway lines, but the republic lost its monolithic stature.

When Perestroika arrived, Bashkortostan was in a poor state. In the general population structure the Russians comprised 39. 27%, the Tatars – 28. 42%, and the Bashkirs only 21. 91% [9].

Therefore, the Bashkirs had to face not only the danger of russification, but also the risk to “dissolve” among the Tatars who were more numerous and more influential. In 1988 an idea of creating a civic organization that would deal with the issues of Bashkirian national revival quickly gained popularity among the Bashkirian intellectual class. In May 1989 the founding convention of the Republican Club of Bashkirian Culture was held in Ufa; Rashit Shaukr, a poet, became the head of the Club [10, 125]. In December of the same year the first congress of representatives of the Bashkirian people was held; 989 delegates took part in its work. The congress approved the statute of the Bashkirian People’s Center “Ural”. Aims, goals and structure of this organization were similar to those of the Tatarian Civic Center. The BPC “Ural” launched a campaign aimed at forcing central authorities to grant Bashkortostan a Union Republic status. At first the attitude of the party leaders of Bashkortostan toward the activities of the BPC “Ural” and the above mentioned campaign was negative. However, with time, when they grasped practical benefits they could get from the sovereignty of the republic, Bashkortostan leaders changed their attitude toward the BPC “Ural” [11].

The BPC “Ural” has played an exceptionally important role in the process of sovereignization of Bashkortostan that resulted in approval of the Declaration of Sovereignty of the Bashkirian Republic by the Supreme Council of the BASSR on October 11 1990. At the same time, the BPC “Ural” put a lot of effort into countering the Tatarian national aspirations which spooked the Bashkirian intellectual class. The position of Tatars who lived in Bashkortostan was quite radical: they demanded that the Tatarian language was given the status of a state official language, along

with the Russian and Bashkirian languages, and that the western regions of the republic were transferred to Tatarstan. In 1991 the Tatarian Civic Center in Bashkortostan even demanded to hold a referendum in the western regions of Bashkortostan seeking popular support there for transfer of those territories to Tatarstan [12].

The situation was further complicated by populistic, and sometimes aggressive, declarations from both Tatarian and Bashkirian sides. Now it is obvious that growth of national movement triggered by the collapse of the USSR, gave rise not only to the development of the national self-awareness and dissemination of ideas of the national identity, but also stirred up latent conflicts between two brotherly Turkic peoples – the Tatars and the Bashkirs.

Chuvashes and their contacts with Finno-Ugrian people

The Chuvashian national movement in 1988-1991 had rather favourable initial conditions. Even though some part of Chuvash people found themselves outside Chuvashia, this republic was the

most monoethnic one in Idel-Ural – 67. 8% of its population represented the title ethnos. Making use of the first benefit of Perestroika – glasnost – the Chuvashes formed a number of social and

political organizations which were independent of the Communist Party. Among them, the most influential organizations were the Chuvash Civic Cultural Center (ChCCC), the Chuvash National

Revival Party (ChNRP), and the Chuvashian National Congress (ChNC). The ChCCC stood for national cultural autonomy and was basically involved in educational activities, dedicating a lot

of time to working with the Chuvashian expatriate communities outside of Chuvashia. The ChNRP and the ChNC did not limit themselves to only cultural agenda and fought for sovereignty of the

Chuvashian Republic [13]. Let us notionally call this group (ChNRP and ChNC) a republican one.

In December 1989 elections to the Supreme Council of the Chuvashian ASSR were held, in which the republicans took an active part. Based upon the results of the elections, the Communists were able to form a parliamentary fraction consisting of 101 parliamentarians (the Parliament had 200 members). The National Democratic fraction which included the republicans headed by a prominent Chuvashian scientist Atner Huzangay consisted of almost 20 parliamentarians [14, 22].

The biggest achievement of the republicans was approval of the declaration of sovereignty of the Chuvashian Republic by the Supreme Council of the Chuvashian ASSR on October 24 1990, and soon afterwards the Law “On Languages in the Chuvashian Republic”. In late August 1991 the Chuvashian Parliament supported by the Chuvashian national movement established the institution of presidency.

In December of the same year the first democratic Presidential election were held. 58. 6% of the total number of voters took part in the election. Parliamentarian Atner Huzangay and Lev Prokopyev, exPrime Minister, representative of the party nomenclature, made it to the second round of the election. Although Hunzagay has won (he received 46% of votes), the election was declared invalid, since the candidate did not win 50% of votes stipulated in the Law [15].

Huzangay’s defeat has been taken by the representatives of the intellectual class as a defeat of the national movement. The first President of Chuvashia became Nikolai Fedorov who completely

surrendered to Moscow’s policy of centralization and behaved rather as a governor and not as a president. This helped Fedorov to stay in the office till 2010. In 2012 the institution of presidency in Chuvashia was liquidated.

Meanwhile Atner Huzangay focused on development and enhancement of the influence of the ChNC (he became the leader of this organization in 1992). At its founding convention the ChNC

came out with a radical program: complete sovereignty of Chuvashia, approval of the Constitution and the Laws “On Language” and “On Chuvashian Citizenship”, in accordance with which Chuvashia was to become a self-sustained republic with presidential government. Finally, the Chuvashian Parliament approved the Law “On Languages in the Chuvashian Republic” but in “compromise variant” to which the Communist majority agreed – both Chuvashian and Russian languages were declared to be the state official languages. In 1993 Huzangay and a group of his followers prepared and made the Chuvashian Parliament approve the “State Program of implementation of the Law “On Languages in the Chuvashian Republic” for the period of time between 1993 and 2000 and beyond”. The Program stipulated a number of measures pertaining to positive discrimination which were to strengthen positions of the Chuvashian language in the republic [16, 2]. The ChNC established effective communication with civic and political structures of the Idel-Ural peoples. In 1994 the organization held a founding convention of the Assembly of the Peoples of the Urals and Povolzhye which was attended by representatives of all influential national faces of the region [17]. In December 1994 the Chuvashian President N. Fedorov found in himself enough courage to criticize Moscow’s policy in the Caucasus region. During his meeting with the representatives of political parties and civic organizations he said: “He who really loves Russia, knows its history, who acts responsibly in politics, may not protect Russia’s territorial integrity by brazenly violating the human rights and sacrificing thousands of human lives, because the principle of territorial integrity is a political category, and the right to sovereignty is about the living people” [18]. Several days after this statement the Assembly of the Peoples of the Urals and Povolzhye greeted creation of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and condemned intervention of the federal army. The Assembly stated that it considers aggression against the Chechens a threat to the Bashkirs, Maris, Mokshanians, Erzians, Bashkirs, Tatars and Chuvashes [19]. Soon afterwards, on January 1995, on initiative of President Fedorov a meeting was held in Cheboksary which was attended by the representatives of the indigenous republics. The aim of the meeting was work out a consolidated position in regard to Moscow’s aggression against the ChRI. The meeting was also attended by the Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Mordovia N. Biryukov, President of the Republic of Mari El V. Zotin, Vice President of the Republic of Tatarstan V. Likhachev, President of the Republic of Bashkortostan M. Rakhimov, Prime Minister of the Republic of Karelia V. Stepanov, Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Udmurtia V. Tubilov. The participants of the meeting emphatically condemned intervention of the federal army and demanded to stop combat operations in Chechnya [20]. In February 1995 a delegation of parliamentarians of the Supreme Council of the Chuvashian Republic headed by the Chairman of the Assembly of the Peoples of the Urals and Povolzhye visited the ChRI and met with President

Dzhokhar Dudayev. During the meeting the Chuvashian delegation voiced support for the Chechen authorities and stated that “the Chuvashian Republic does not recognize the State Duma of the

Russian Federation as its parliament” [21, 59]. In the beginning of 1996, after a series of terrorist acts the blame for which Moscow put the blame on the Chechen resistance movement, the position of the Chuvashian top authorities in regard to the Chechen war underwent changes. However, in the spring of the same year the Parliament of Chuvashia found courage in itself to pass a declaration in regard to the situation in Chechnya calling for immediate cessation of hostilities [22].

In 1996, following the Russian presidential election in Chuvashia which proved to be Yeltsin’s debacle (only 26. 6% of the votes), N. Fedorov allowed himself to launch some arrows of criticisms

at the Chuvashian people. As a result, a conflict between the republicans and the President broke out. However, in 1997 Gennady Arkhipov became the head of the ChNC. During his time in the office the organization lost all remnants of independence and gave up on opposing Moscow.

Peculiar features of the Finno-Ugrian revival

The national revival of the Finno-Ugrian peoples in 1988-1991 on the territory of Idel-Ural was not as politically prominent as in the case with the Turkic peoples. However, the Finno-Ugrians

of Idel-Ural were able to hold their own national congress: the Udmurts in November, the Erzians and the Mokshians in March 1992, the Maris in October 1992, the congress of the Finno-Ugrian

peoples of Russia in May 1992 (Izhevsk). All those congresses carried similar resolutions which called for democratization of political and social life in the republics, national revival of the FinnoUgrian peoples. Certain influence on formation of the attitudes and opinions which dominated at the congresses, especially among the national intellectual class was exerted by Estonia, since many representatives of the Finno-Ugrian republics of Russia were alumni of Tartu University [23].

The Maris were the people who fought for their political rights more actively than others. They created several national organizations: Mari Ushem Youth Alliance (1989), U Vii (1989), Kugeze

Mlande (1991). The latter called for separation of Mari El from the RF and complete state sovereignty. The number of Kuguze Mlande members always was small, but the organization proved to

be very active. Moderate Mari Ushem became pan-national Mari organization which united thousands of teachers, scientists, cultural workers.

It should be noted that the Mari people is comprised of several sub-ethnoses. Usually Mari are classified into Hill Mari and Meadow Mari. Each of these sub-ethnoses has its own distinct dialect

(some researchers consider these dialects two separate languages). Hill Mari are less numerous, they embraced Christianity a long time ago and almost completely renounced their pagan beliefs. The rest of the republic is inhabited by Meadow Mari who are pagans. According to the poll conducted in 2000-2003, in the Republic of Mari 7% of population are pure pagans, 60% practice both Christian religion and pagan rites, and only 30% are Orthodox Christians who are predominantly ethnic Russians. Mari expatriate communities scattered around other Idel-Ural republics are descendants of pagans who fled from forcible Christianization. Thus, 90% of Mari diaspora on the territory of Idel-Ural are practicing pagans [24].

In 1990 the local Parliament passed declaration of sovereignty and announced establishment of the Mari Soviet Socialist Republic. Soon afterwards institution of presidency was introduced in the

republic, and in December 1991 the presidential election was held. The pre-election campaign and its results were very similar to those of Chuvashia: participation of a representative of the national movement in the election, his defeat and concentration of power in the hands of former representatives of the party nomenclature.

After the political fiasco the Mari organizations focused on civic activities. Simultaneously, the ideas of revival of Mari identity were actively promoted by means of religion. Traditional religious

cults had significantly stronger influence on the Maris than they did on Erzians, Mokshanians or Udmurts. All influential Mari organizations, such as Mari Ushem, U Vii, Kugeze Mlande combined

social activity with revival of paganism. These organizations were able to register the first big pagan association “Oshmari-Chimari” (“White mari – Pure mari”) in Russia in 1991. In the same

year the first collection of various pagan prayers in Mari language was published [25]. Notwithstanding the fact that the Mari people belong to the Finno-Ugrian group, they look to Tatarstan as

an example to follow in order to implement their plans of revival. Numerous terms and even some religious postulates were borrowed by the Maris from Islam through the Tatars.

Following the collapse of the USSR, the Mari paganism began to play a significant role in the political life of the republic. The same cannot be said about Erzia-Mokshania and Udmurtia. President

Vladimir Zotin elected in 1991 was a Hill Mari. He invited Kazan Bishop Anastasy to his inauguration. This initiative met with strong opposition from the paganist lobby in all State branches. The

pressure on Zotin was so strong that he had to invite also the Supreme kart (animist priest) of Oshmari-Chimari Aleksandr Yuzikain who was placed next to the Orthodox bishop in the VIP box. As a result, the President of Mari El received blessings in both traditions – orthodox and pagan.

The national revival of Udmurtia was proceeding in the wake of the neighbours and had but a few manifestations worth mentioning. When the USSR was collapsing, percentage of the Udmurts in the population structure of Udmurtia was only 30% (compare with 52% in 1926); that is why the Udmurts could neither occupy key managerial positions in the republic nor dictate their own “rules of the game” in politics [26]. The characteristic feature of the national political revival of the Udmurts in 1988-1991 was the intensified cooperation with the international Finno-Ugrian movement: establishment of close contacts with civic organizations and funds based in Estonia, Finland and Hungary; fast development of the Udmurtia literature (especially translations).

Like in Udmurtia, the demographic situation in Erzia-Mokshania was complicated – the major part of Erzia and the Moksha people was living elsewhere; these peoples comprised only 32. 5%

of the population of the republic. At the same time, here the process of the national revival proceeded faster than in Udmurtia due to extremely weak positions of Moscow Patriarchate in Mordovia – only 10 parishes in 1987 [27].

Return of the Erzians and the Mokshians to their national identities met with the challenges presented by russification, urbanization and demographic crisis. But more challenges were to be faced. Some part of the national elites of the Moksha people and, to a lesser extent, of the Ezrians came out with a concept that erzia and moksha are sub-ethnoses of the single Mordovian people. This concept met with fierce opposition from the representatives of the Erzia national movement who saw the Mordovian project as an instrument of assimilation of the Erzians into the Russian identity.

In the spring of 1989 the republic saw the appearance of Velmema Civic Center that quickly gained popularity and gathered both Ezrians and Mokshanians under its flag. Soon after its creation

some active members of the Center felt that rigid frames of the national cultural activity do not suit them, and Velmema broke up. Moderate members set up an organization called Vaigel’ which is engaged in activities connected with the revival and dissemination of national traditions; more radical members created the Erzia-Mokshanian civic movement called Mastorava which deals not only with the national revival of erzia and moksha but also strives to represent their interests in the power structures.

Due to the activities of Velmeme, Vaigel’ and Mastorava societies the situation in relation to implementation of the rights of erzia and moksha in Mordovia underwent significant changes. The

National Theatre was opened, the National Culture Center Department was opened, the Law “On Languages” was passed, and the work with expatriate communities was on the rise. The above mentioned organizations became a “talent pool” for new social organizations of erzia and moksha: Od Vii, Erziava, Litova and Yurkhtava, Mastorava and Erzian Mastor newspapers. Activities of all mentioned organizations and societies allowed Erzia and Moksha national movements to switch from the ethnographic phase to political phase in their development.

Religious revival which proceeded in two opposing directions – return to traditional monotheistic religion (Ineshkipazia) and development of Lutheranism – has played an important role on the process of de-russification, especially among the Erzians.

In the early 1990s the leader of the Erzia national movement was Mariz Kemal who has become the main ideologist of the “Two languages – two peoples” concept. This concept did not recognize

the existence of the Mordovian people as a union of sub-ethnoses – erzia and moksha [28]. Mariz Kemal worked to set up societies of traditional erzia beliefs. This phenomenon first appeared after establishment of the Mordovian Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROCh) (1990). At that time the Erzia intellectuals came out with an idea of using the national language at religious

services. They hoped to be able to revive the erzia identity at least within the ROCh. The failure of those hopes has radicalized the erzia believers, stimulated the national intellectual class to work

toward the revival of ethnic religion – religion of the god Ineshkipaz.

In 1992 Ms. Kemal was able to find sponsors from among the erzia entrepreneurs who financed the first national prayer session in one of Mordovian villages. Kemal was pronounced Ozava (erzia

priestess), and the erzia national faith issue became the subject of discussions by scientists and theologians in Saransk [29].

In parallel with the revival of Ineshkipazia in Mordovia, the Moksha-Erzia Evangelic Lutheranian Church has been established.

In late 1980s a talented erzia ethno-futurist artist Andrey Alyoshkin moved to Leningrad. There he made a number of paintings in which he tried to reveal the essence of the ancient beliefs of erzia and moksha. A Lutheran pastor Arvo Survo – a leader of the religious revival movement of the Ingrian Finns – noticed the talented artist and converted him to Lutheranism.

After Alyoshkin returned from Leningrad to Saransk, he received nationwide recognition. He was elected the Chairman of the Artists’ Society of Mordovia, he became one of the leaders of the Society for Studies of Finno-Ugric Culture. The famous artist was able to convince several representatives of Saransk intellectual class that the future of Christianity in Mordovia lies with Lutheranism. In 1991 the Mordovian Martin Luther Christian Church was established. The activists demand that the Church is given a plot of land for construction of the temple. Arvo Survo holds his first services. Finnish Lutherans promise financial support. The artist’s brother Alexey becomes the first clerk of the church. However, shortly after its registration the church faces numerous challenges: the ROCh launches an aggressive campaign against the “Finno-Ugric sect”, and soon the Finns offended by wayward behaviour of the Erzians and the Mokshanians withdraw their support. The conflict with the Finns was caused by the abysmal differences in the approach to activities of the church and its sacraments. The Alyoshkin brothers did not want to adhere to traditional protestant principles; they also rejected new secular trends which exist in the Finnish Lutheranism. On the one hand, they tried to sacralise the activity of the new church, and on the other hand, they get closer to people by combining elements of orthodox Christian religion (in particular, revering icons) and national traditions (erzia and moksha national attire, folk songs,

etc. ) in religious services.

Lutheranism left a significant imprint in the contemporary history of erzia and moksha. Even today on the territory of Erzia-Mokshania there are several parishes which belong to the Ingrian Evangelic Lutheran Church.

Moscow’s struggle against the national movements of Idel-Ural

The major part of national and political achievements of the Idel-Ural peoples is the result of a short period of relative freedom in the USSR and later in the Russian Federation from 1988 to 1999.

After Vladimir Putin came to power, the Kremlin headed for rigid centralization. The most independent and rich constituent entities of the federation, first of all Tatarstan, fell victims to this policy. In 1998 the Tatar newspaper Altyn Urda was shut on accusations that it stirred up national hatred. For some time the newspaper was published unofficially, but eventually the authorities closed it completely. In 2001 the Russian legislation banned activities of the national political and national parties. Numerous civic organizations and movements of the indigenous peoples stopped their activities due to legal persecution and pressure from security services. Among them were the Party of Tatar National Independence Ittifak, the Mari Kugeze Mlande, the Chuvashian National Revival Party, etc. In 2002 the founder of the Erzia Od Vii organization Yovlan Olo suddenly died in Saransk falling victim to some mysterious disease.

During the first ten years of Putin’s time in the office, only in Tatarstan 690 Tatar schools were liquidated. Leaders of Tatar national movement Fauzia Bairamova, Rafis Kashapov, Nail Nabiullin were legally persecuted.

Sovereignty of all Idel-Ural republics was significantly limited. The institution of presidency was abolished everywhere, except for Tatarstan.

In 2018 amendments to the Federal Law “On Languages” have been introduced. In accordance with them, the official state languages of the national republics ceased to be mandatory for teaching in general education schools. A lot of teachers of Tatar, Bashkirian, Chuvash and other languages lost their jobs because of these amendments.

However, notwithstanding total control over any manifestations of political and civic activities, the struggle for implementation of the rights of the indigenous peoples of Idel-Ural continues. In the

spring of 2018 a group of political emigrants announced the establishment of the Free Idel-Ural civic movement which intends to wage nonviolent struggle for sovereignty of the six republics of Povolzhye Region [30].

Despite the fact that the current political climate in Russia does not make it possible to speak of any serious transformations inside the federation, the national movements of the Idel-Ural peoples continue their activities in conditions of total control and unprecedented pressure. Therefore, Idel-Ural remains to be a hidden geopolitical factor which may manifest itself in conditions of today’s political unrest.

References:

1. Population of the Russian Federation across municipal units as of January 1, 2018

2. Hellenic Statistical Authority. Estimated population / 2018

3. M. Valeyev. National book’s noble mission. / Mudaris Valeyev. // Republic of Tatarstan – 2006. – No 101

4. “Tatarization of the World”: What one should know about translations into Tatarian language

5. Information about living conditions of population. // Analytical materials. – 2017. – No 12.

6. Tataria: disposition for federalists // Panorama. – 1992. – No 2 (32).

7. Statement by the President and the Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Tatarstan of June 24, 1993 / White Book of Tatarstan. Road to Sovereignty // Panorama-Forum Magazine. — 1996. — No 8 (Special issue).

8. Ilnar Garifullin. Bashkirian enclaves of the Southern Urals: how borders of Bashkortostan and Chelyabinsk Regions were drawn

9. The 1989 All-Union Population Census. Composition of population according to nationality across regions of Russia

10. A. M. Buskunov. New Bashkirian national movement (to the 15th anniversary of creation of Bashkirian civic organizations /. M. Buskunov. – Ufa, 2005

11. M. N. Guboglo. Ethno-political mosaics of Bashkortostan. Essays. Documents. Chronicles. Volume II. The Bashkirian national movement

12. Ilnar Garifullin. Tatar language in Bashkortostan: historical background

13. M. Antonov. You shall not make for yourself an idol // Cheboksary News. – 1992. – March 14

14. V. R. Filippov. Chuvashia in the 90s: ethno-political essay / V. R. Filippov. – Moscow: The Russian Academy of Sciences, 2001. – 250 p.

15. Creation of institution of presidency and the first presidential elections in Chuvashia

16. The State Program of implementation of the Law “On Languages in the Chuvashian Republic” for the period of time between 1993 and 2000 and beyond. // Soviet Chuvashia. 1993. July.

17. Spirit and ideas always win in the end. Interview. – Irekle Samsh – 2012.

18. Chronicles // Soviet Chuvashia. 1994. December 13

19. Declaration of the Assembly of the Peoples of the Urals and Povolzhye of December 17, 1994

20. Joint declaration by the participants of the meeting of the heads of the republics of the Russian Federation and members the Public Committee “Concordance for the sake of Motherland” // Soviet Chuvashia. 1995. January 6

21. V. R. Filippov. Chuvashia in the 90s: ethno-political essay / V. R. Filippov. – Moscow: The Russian Academy of Sciences, 2001. – 250 p.

22. O. Gorchakov О. For peace and concordance in Chechnya // Soviet Chuvashia. 1996. March 6

23. National congresses: historical background

24. Aleksandr Schipkov. What Russia believes in. Lecture 7. National paganism. Mordovia, Chuvashia, Udmurtia, Mari El

25. N. S. Popov. The Mari prayers and incantations. Yoshkar-Ola, 1991

26. The 1989 All-Union Population Census. Composition of population according to nationality across regions of Russia

27. A. Schipkov. Religious beliefs of moksha and erzia

28. Mariz Kemal. Min’ – erzyat’!

29. Erzia Rasjkenj Ozks ceremony as witnessed by a Chuvash

30. Pavlo Podobied. How to find the way out of the Orenburg corridor